First, some basics. Most of Earth’s carbon is stored in rocks and the rest is in the ocean, atmosphere, plants, soil, and fossil fuels. Flows of carbon from reservoir to reservoir make up the carbon cycle, which has fast and slow components.[1]

Photosynthesizing plants and plankton capture and accumulate CO2 from the atmosphere and pass it up the food chain to other life forms. Respiration by organisms and eventual death and decay return CO2 to the air or into soil. Carbon moves through this biological cycle in years to decades.[2]

The slow or rock cycle involves carbon in the air falling in rain, rock weathering, and erosion with sediment and organic debris flowing into the ocean. Carbon from these sources and carbon dissolved from the air can be made into shells. Shells and sediment slowly sink to the bottom of the ocean and cement into limestone rock. This is how 80% of carbon-containing rock is made. The rest comes from living things buried in mud, compressed by heat and pressure, to form coal, oil and methane gas. Carbon returns to the air through volcanic activity.[2] Geochemical processes take hundreds to millions of years.[1]

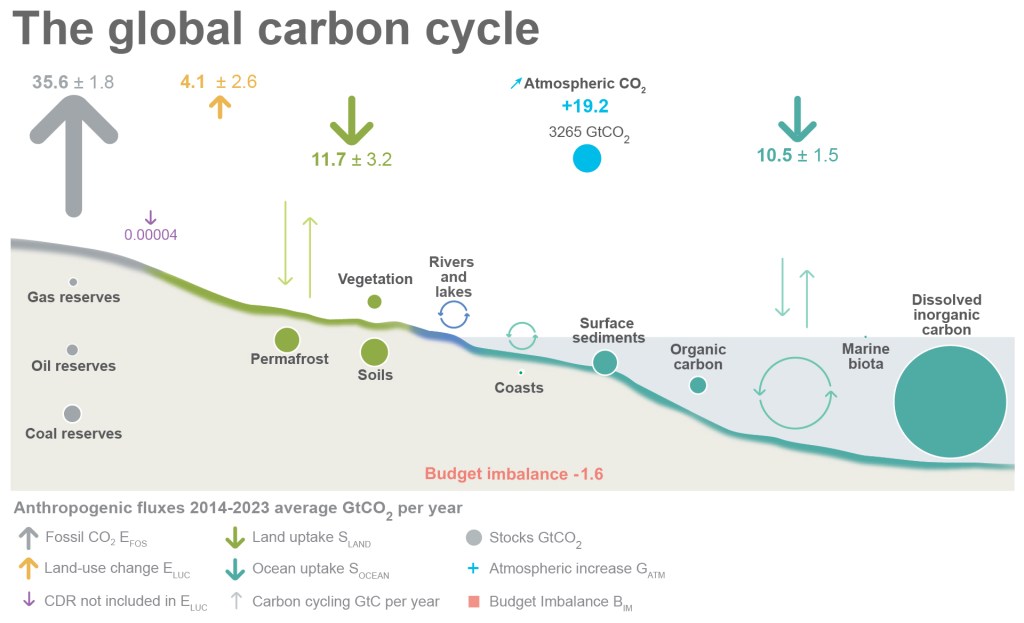

In this diagram of what the carbon cycle looks like currently, stores of carbon appear as shaded circles and arrows show carbon movement between reservoirs, as average annual fluxes for the past decade 2014-2023.[3] A lot of carbon cycles into and out of the atmosphere naturally, 130 gigatonnes of carbon per year (GtC/yr) from land and 80 from the ocean. Human activities generate emissions of 10.8 GtC/yr, 9.7 from fossil fuels and 1.1 from land-use change such as clearing forest for farmland.[4] After land and vegetation absorb 3.2 and the ocean 2.9 GtC/yr, there is still 5.2 GtC/yr added to the atmosphere, with a small “budget imbalance” for methodology variances and unknowns. Global warming is tied to atmospheric CO2; in this context, carbon sources or emitters add carbon to the air, while carbon sinks absorb or remove carbon from the atmosphere.

This is just a snapshot. Fluxes and reservoirs are not constant, and are altered by human activities and global warming.[5] Different parts of the carbon cycle respond in different ways and at different rates. The fast carbon cycle is evident in the CO2 fertilization effect, when increased CO2 spurs plant growth and CO2 capture through photosynthesis. This may be boosted by longer growing seasons, but is limited by water and nutrient availability. Deforestation by humans reduces the land sink, while planting new forests or allowing forests to regenerate adds to it. Natural disturbances such as drought, insects and disease, and fires, exacerbated by climate change, weaken the land sink. Thawing turns permafrost soil from carbon reserve to carbon source. The net effect of these complex interactions is tough to calculate, because there is so much variation in landscapes, in plant and soil composition, and in how global warming manifests locally.[6,7] Tallies of human land-use change are sometimes inconsistent.[8,9]

The ocean is also a major carbon sink. More carbon dissolves into the ocean as atmospheric CO2 increases. An unfortunate consequence is acidification that harms shell-building organisms such as coral. The ocean, however, will absorb less carbon as ocean temperatures rise and chemical buffering capacity wanes.[6] The movement of carbon into surface and deeper layers of the ocean is affected by too many other factors to enumerate here.[10]

The natural carbon cycle maintained an equilibrium for some 10,000 years.[11] We are mucking up the natural carbon cycle by releasing fossil carbon on human rather than geologic timescales, exceeding its capacity to maintain equilibrium in meaningful timeframes.[12,13] Roughly half of all man-made emissions have been absorbed by natural sinks so far. What comes next? Terrestrial and ocean sinks are projected to take up more carbon, but the fraction of emissions that is absorbed will decline.[6]

Carbon is not “bad;” it is the stuff of life. Land plants and ocean are not just carbon sinks; they are life-supporting ecosystems. But fossil emissions are out of whack with the natural carbon cycle, and ruinous. You know what I’m going to say next. The fix is to retire fossil fuels and preserve our natural world.

REFERENCES

- Carbon cycle. Wikipedia, accessed 31 Jul 2025. (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon_cycle)

- Riebeek H, Jun 2011. The carbon cycle. (https://www.earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/CarbonCycle)

- Friedlingstein P et al, Mar 2025. Global carbon budget 2024. (https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-17-965-2025). The carbon cycle is measured in units of carbon atom weight, so that it doesn’t matter what molecular form it takes. 100 billion metric tons of carbon = 1 gigatonne (GtC) = 1 petagram (PgC). The excerpted Figure 2 and my write-up consider CO2 only and not methane or other greenhouse gases.

- Dhakal S et al, 2022. IPCC sixth assessment report, working group 3, Section 2.4.2.5 AFOLU sector. (https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg3/chapter/chapter-2/). AFOLU=agriculture, forestry and other land use, encompassing deforestation, afforestation, logging and forest degradation, peat burning and drainage.

- McKinley GA, 2025. Carbon and climate. (https://galenmckinley.github.io/CarbonCycle/) Scroll down for an animation of changing sources and sinks, “Cumulative anthropogenic carbon since 1850.”

- Canadell JG et al, 2021. Global Carbon and other Biogeochemical Cycles and Feedbacks. In Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. WGI AR6, Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. doi: 10.1017/9781009157896.007 (https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg1/chapter/chapter-5/). In section 5.2.1.5, see Figure 5.12 for pre-industrial vs anthropogenic fluxes and Table 7 decadal changes.

- Schimel D, Nov 2007. Carbon cycle conundrums. (https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.0709331104). Evolving concepts of major influences on sinks.

- Peters G, Nov 2024. Separating land carbon uptake from net-zero emissions. (https://cicero.oslo.no/en/articles/separating-land-carbon-uptake-from-net-zero-emissions)

- Asayama S, De Pryck K, Hulme M, 2022. Controversies. In A Critical Assessment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/critical-assessment-of-the-intergovernmental-panel-on-climate-change/controversies/6502E4860EB8CE666794EC21156C656D) See Box 16.2 on land-use change.

- How the ocean absorbs carbon dioxide. Multiple contributors, 2008. In World Ocean Review 8. (https://worldoceanreview.com/en/wor-8/the-role-of-the-ocean-in-the-global-carbon-cyclee/how-the-ocean-absorbs-carbon-dioxide/)

- Mulhern O, Aug 2020. A graphical history of atmospheric CO2 levels over time. (https://earth.org/data_visualization/a-brief-history-of-co2/). CO2 and temperature from 500 million years ago to present. Ice core data goes back 800,000 years. (The Earth is 4.5 billion years old.)

- Moseman A with Rothman D, Jan 2024. How much carbon dioxide does the Earth naturally absorb? (https://climate.mit.edu/ask-mit/how-much-carbon-dioxide-does-earth-naturally-absorb) The natural carbon cycle balances itself, but very slowly, over centuries or millennia.

- Bralower T & Bice D. Overview of the carbon cycle from a systems perspective. Part of Earth in the Future. (https://www.e-education.psu.edu/earth103/node/1019) Residence time (average time spent in reservoir) and response time (how long to return to a steady state).

September 7, 2025: Edits were made to the second to last paragraph beginning “The natural carbon cycle” and to comments in reference 6.

Leave a reply to bethrobertson58 Cancel reply